In our previous blog about heat acclimation, we spoke about the effects of warmer temperatures on endurance athletes, as well as on intermittent and racket sports such as football and tennis. Over the last decade, the consensus is that heat acclimation is the most important intervention to reduce physiological strain and optimise performance in a range of sports. With this in mind, let’s delve a little deeper into why heat acclimation is becoming a vital component of athlete preparation – both for hot competitions, and cooler ones too.

International sporting competition is heating up…

Not in the metaphorical way – I mean sports competitions are literally getting hotter. With global warming on the rise, alongside the globalisation of elite sport taking events into new, hotter environments, it is clear why greater foresight is being used to tackle how the climate might affect the safety and performance of elite athletes. As sporting organisations make heat mitigation strategies more commonplace, is there more that athletes themselves can do to optimise their performance in the heat and in wider competition?

Competitions in mild climates such as the London Marathon have recently experienced the impact of rising temperatures. A sweltering 24.1 degrees Celsius in 2018 rendered many runners unprepared and exposed to the risks associated with heat stress – this isn’t really surprising when you consider the optimal temperature for marathon running is 10-12 degrees Celsius.

Tennis is also seeing more record-highs, with an analysis finding that Grand Slam temperatures have been steadily increasing since 1988. While research is important in identifying such trends, what is more indicative of these hostile playing environments is that players themselves are beginning to struggle. Last year, Daniil Medvedev was playing in the quarter finals on the hottest day of the U.S. Open, where an off-hand comment took the media by storm. In the middle of his match, he walked over to a camera and said, shaking his head: “One player is gonna die”.

Medvedev and others had been playing in 35-degree heat, with the majority clearly suffering in the high temperatures. His statement drew the world’s attention to how such conditions not only impact performance, but could potentially be dangerous to those not appropriately prepared.

It’s not just the athletes who at are risk either: in 2015, a ball boy collapsed in the heat during the hottest day in Wimbledon history, suggesting heat precautions should also be considering those working at these events. With increasingly longer seasons in sports like football and rugby, pushing more competition into the summer months, perhaps Medvedev was right to highlight that elite sportspeople are not immune to hot conditions and must take this into account.

While global warming is a known risk, an understated factor is the growing prevalence of competitions in developing tropical/desert countries. I’m sure everyone recalls Qatar controversially hosting the FIFA Men’s World Cup in 2022. The tournament was only permitted to take place there in winter where it was coolest, and even then it was still a humid 30+ degrees Celsius; players’ performance was noticeably hindered by the climate. Other examples include the hottest Olympics on record in both Rio and Tokyo, alongside the World Athletics Championships venturing out to Doha in 2019.

How can we reduce the risk?

Event organisers are doing their best to ensure competition is even possible in these warmer climates, often having to go to extreme measures. For example, the Olympic marathon in Tokyo had to be moved to a completely different location, being held in Sapporo instead of Tokyo city as it was 5 degrees cooler. Meanwhile, more stadia are being equipped with state-of-the-art air conditioning to protect both the competitors and the spectators from the heat.

Personally, I would argue whether it is worth hosting athletes in places where such drastic changes need to be implemented; surely our goal is to encourage excellence, instead of putting athletes in conditions that hinder elite performance? Nonetheless, this trend is likely the future of sporting competition. While institutions figure out the logistics around making competition safe, athletes must therefore take performance optimisation into their own hands. Although we cannot determine where events are held, or what the temperatures will be on the day, athletes are in control of how they prepare for such circumstances. This is where heat acclimation comes in.

Heat Acclimation is key!

As we mentioned at the start: heat acclimation is the most important intervention to reduce physiological strain in the heat.

The goal of athletes competing in hot environments is to maintain the highest possible intensity whilst limiting the rise in core body temperature. When intensity is too high for their physiology to cope with, an athlete faces a dilemma. If they continue at the same intensity, their core temperature will continue to rise. This can stimulate excess sweating and consequently water and salt loss, which puts an athlete is at risk of heat exhaustion. If core body temperature is left to rise above 40-degrees C, heat exhaustion can develop into heatstroke, which is a serious and potentially fatal condition. The other option is to reduce intensity to a level where an athlete can continue whilst sustaining a stable core temperature. While this is obviously preferable over heatstroke, it would also be to the detriment of performance, which goes against what athletes set out to achieve in competition.

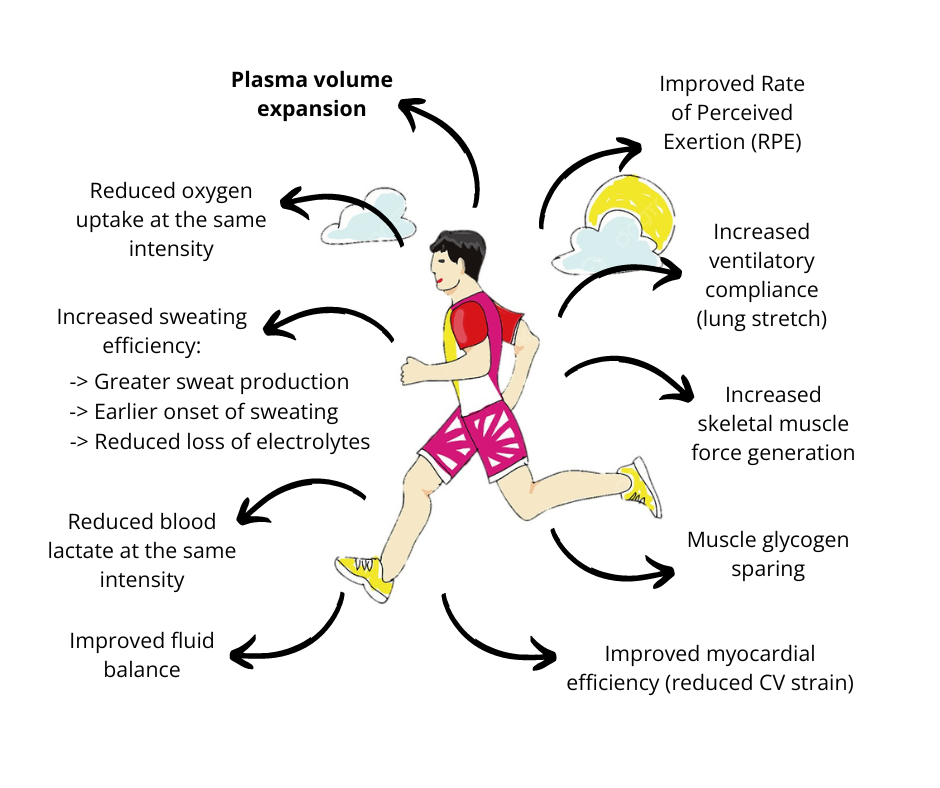

To combat this dilemma and enable core body temperature to remain stable without compromising intensity and performance, athletes must improve their ability to deal with the heat through heat acclimation. The figure below shows adaptations which facilitate how the body achieves this.

When under thermal stress, the body diverts more blood to the skin to offset heat produced during metabolism (e.g. muscle contraction) to the surrounding environment via radiation, in an attempt to prevent the continued rise in core temperature. This, however, means that less blood is available to be sent to the working muscles, which impairs oxygen delivery and the removal of by-products like lactate, and so limiting the output of muscles.

Plasma volume expansion is likely the most significant adaptation from heat acclimation and has the most research supporting its positive impact. Having more blood plasma increases blood volume, which means that the body can supply more blood to both the muscles and the skin, so the athlete doesn’t have to prioritise cooling mechanisms over performance. Improved fluid balance (our control of body water and electrolytes) also means we can sweat more, in turn allowing more heat to be dissipated from the body via evaporation and delaying the rise in core temperature.

All the physiological adaptations made in response to heat acclimation have a resultant effect on core body temperature. At the same intensity, core temperature remains lower, not only protecting the athlete from potential heat illness, but also allowing them to perform better under hot conditions.

Alongside physiological adaptations it is also worth noting the impression heat acclimation has on athlete psychology; we found first-hand here at The Altitude Centre that even after a single heat session, athletes felt they were better able to deal with the heat and that it affected their performance less, with a lower rate of perceived exertion at the same core temperature.

Hotter competition, no matter the reason, is making the following very clear: heat acclimation is becoming a necessity. This isn’t just for elite athletes either; any individual undertaking an event in the heat should consider incorporating heat acclimation as a matter of safety as well as performance. Despite this, research shows that athletes from both intermittent and endurance sports are not currently utilising heat acclimation as well as is recommended. Only 15% of athletes underwent heat acclimation before the 2015 World Athletics Championships in Beijing, despite the knowledge that conditions were going to be hot and humid. As popular events are ever threatened by high temperatures, it’s your job to take performance into your own hands and make heat acclimation an integral part of your preparation.

Further application of Heat Acclimation

Looking at the adaptations labelled above, you might begin to think: wouldn’t some of those also be useful for everyday performance? And you would be correct! Research suggests that incorporating heat acclimation can improve performance in temperate environments too.

Although the field is relatively new and has some conflicting research, there is sound reasoning behind this notion. Increased blood plasma volume leads to increased cardiac output (the volume of blood pumped out the heart per minute), which in turn enables greater VO2 at a given intensity. Greater VO2 means increased oxygen delivery and as a result, more efficient (i.e. aerobic) energy production. Similarly, reduced muscle oxygen uptake and lactate production at the same intensity, combined with muscle glycogen sparing, means that in whatever the conditions, the body is less wasteful with its resources. An increase in the force produced by skeletal (limb) muscles would benefit powerful movements, while increased ventilatory compliance allows greater lung volumes and so greater ability to get oxygen into the body.

A recent study on national-level rowers showed that 10 hours of heat acclimation led to a large improvement in 4-minute Time-Trial performance in temperate conditions. Although this was not statistically significant, the difference in time found between the groups would be enough to separate the medal positions within elite rowing competition, which gives good relevancy to the findings. In sports like rowing, where adaptations like increased VO2 max and reduced blood lactate at the same intensity are correlated with performance, it makes sense that heat acclimation could be the cause for such improvements.

This all indicates that heat acclimation has the potential to benefit a much wider range of athletes, in lots of events and climates. Since heat acclimation protocols are done over a relatively brief period of 4-14 days, it has been suggested that athletes should use it as a short-term intervention to improve performance. If you wanted a last-minute boost, then this is the way to do it!

Where can I do Heat Acclimation?!

In the past, heat acclimation has been confined to elite sport, due to the expense and logistics of incorporating such training, however nowadays it is much more accessible to the everyday athlete. Here at The Altitude Centre, we offer heat acclimation in our environmental chamber which can simulate both dry and humid heat up to 45-degrees C. So, whether you are planning on running across the desert in the Marathon Des Sables, or simply want to ensure that a warm day isn’t going to scupper your attempt at a personal best, heat acclimation is key!