In the 1920s, South African mines were booming. The Golden Arc, a dried up sea bed spanning from Johannesburg to Welkom, was proving a literal gold mine, and it became big business. As mining companies became ever more greedy to access deeper reserves, the mines had to be extended up to a mile below the Earth’s surface where vast deposits could be found. Mine operators, or rather the miners themselves, had a problem however. At such depths, the rock through which miners were tunnelling superheated the air to upwards of 60 Celsius; not just unpleasant working conditions, but conditions that lead to 26 heat stroke deaths in one mine alone in 1926. The combination of exhausting labour and extreme heat was a problem that had to be overcome. To begin with, new miners were ordered to share one axe between two, such that each man was given rest and couldn’t exhaust himself from endless work. While that helped, it didn’t get to the route cause; miners were still struggling with the heat and 20 more died between 1926 and 1931. Then a doctor was brought in to oversee the situation. He devised a simple but effective test that showed some individuals were more susceptible to developing heat illness than others, and crucially he identified that he could quickly improve heat tolerance by placing miners in a room that simulated some of the conditions they would experience in the mine for short periods of time. The result was highly effective, and soon the idea took off such that by the outbreak of WWII and jungle warfare, it was commonplace for soldiers to spend time getting used to the heat before heading into war. Over the decades this process has been scientifically refined, and applied to those competing in extreme heat to facilitate high performance in these conditions. Now, heat acclimation is considered to be an essential component of preparation for competition in anything other than perfect conditions.

What Constitutes ‘Hot’?

Before getting into the hows and they whys, it’s probably important to understand what we actually mean by hot. I think we can all appreciate that there are several events that take place in extreme heat. Think of the Marathon des Sables, a 5 day ultra marathon across the Sahara, or the Ironman Kona, a 140.6 mile swim, bike, run odessy in hot and humid Hawaii. These events pose an obvious heat challenge. But recent evidence shows that we don’t need to be in such extreme environments to feel the effects of the heat. Indeed research shows that marathons run between 15-20 C are slower than those between 10-15 C, and anyone who has tackled Alpe d’Huez on two wheels on a hot day can atest to the challenge of baking in relatively moderate conditons. Now, as the effects of climate change become ever more aparent, more sporting events are being conducted in hot conditions (we’ve even seen the London Marathon take place in 25 degree heat in recent years!), meaning that being well prepared for the heat is becoming more important than ever. While early research focussed on heat in middle and long distance events, more recently we’ve a growing focus on intermittent sports like football & rugby, and racket sports like tennis, which are all increasingly being played in hot conditoins.

What is Heat Acclimation?

When World Athletics announced that their 2019 Championships would be hosted in Doha, the marathon runners became concerned. Although the athletics stadium was air conditioned, the marathoners would be out in the dessert for their race which, even with a 2am start time, meant it was going to be hot. Only a year before at the Commonwealth Games, Scotland’s Callum Hawkins had been leading the race by over 2 min when he collapsed with heat exhaustion in the swealtering conditions of Australia’s Gold Coast. Learning from the experience, his preparation for Doha included a stint in the heat in Mallorca, and a home jerry-rigged heat tent (there aren’t many heat chambers in Scotland!) in the weeks prior to the race. Come race day, while others were seeing their race plans blown out the water by the extreme heat, Hawkins ran a controlled race to finish within 2 min of the time he set in a considerably cooler London not 6 months earlier.

In the interim, his self-styled heat training had fundamentally changed how his body responded to exercise in the heat.

When we exercise in hot conditions, performance is impaired. Remember, we are not only trying to mitigate the effects of hot and humid environments, but the heat generated by the body during exercise; we are only about 25% efficient, so cycling at 250 W generates an additional 1000 W of heat! The reason behind this is multifactoral, but comes down to one key thing; core body temperature.

As core temperature increases, the body is desperate to prevent it reaching a critically high level. We redirect blood towards the skin to allow heat to conduct and convect away from the core and into the air, and we sweat to speed up that process. This takes vital oxygen and nutrient carrying blood away from the exercising muscles meaning we are forced to slow down, and sweat draws water from the blood, thickening it and elevating heart rate at a given intensity. Suddenly, what was once manageable is now unsustainable, and performance is impacted. Research has consistently shown that as we approach 40 C, we slow ever more to prevent going over this critical heat threshold above which we eventually exhaust and terminate exercise.

However, the body is highly adaptable, and when we expose our body to hot conditions our ability to cope with the heat improves. We produce more blood plasma which enables us to sweat more, and from earlier into exercise, and means we can send blood to the skin for cooling and the muscle for exercise at the same time. Not only can we stay cooler for longer, but our perception of the heat also improves, and other structures like our heart and gut are better protected from the heat. In all, our exercising core temperature is lowered, meaning the upward drift towards 40 C is limited and performance improved.

Returning to Hawkins, where before, on the Gold Coast, the Scot’s core body temperature sky-rocketed and caused eventual shut down, in Doha he was now able to more effectively cool his body, and keep his core body temperature in check for longer, minimising the effect on performance.

How Do We Acclimate To The Heat?

The good news is that heat acclimation is relatively straightforward, and in the scheme of things, quite quick. The body is highly adaptable, rarely more so than in response to hot conditions.

Research has shown that a maximal adaptation can be achieved with ~15 heat acclimation sessions, but meaningful adaptation can be achieved in between 5-10 sessions across 2-4 weeks. The type of exercise doesn’t matter too much, meaning cyclists should probably cycle, and runners should run (unless adding heat training on top of an already heavy running schedule, in which case cycling might help control overall training load). However, with modern tech, we can be a little more nuanced in heat acclimation approaches.

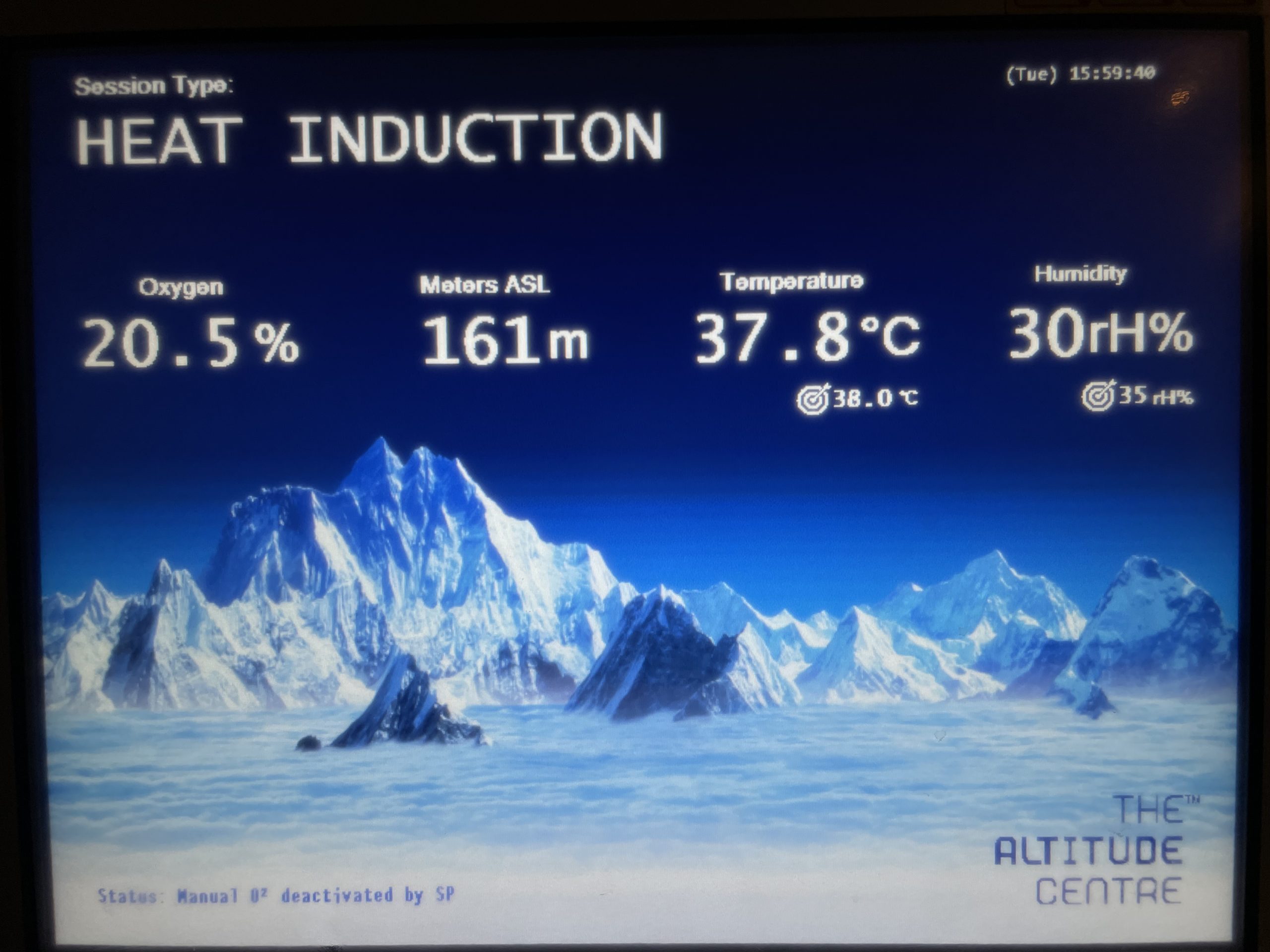

At The Altitude Centre, we use a protocol called isothermic acclimation. This means that in your first session we will conduct a heat ramp test to identify your personalised heat training zone (i.e. the core temperature that we need to get you to in order to illicit the greatest adaptation). Then, in subsequent sessions we will work you at the speed or power required to hit your individualised heat training zone, all the while monitoring your core temperature in real time to ensure you are getting just the right dose of heat. Over time, and as your body adapts, we will see the intensity required to do so rising, showing you are able to work harder in the heat!

What Does It Mean For Me?

Anyone expecting to compete in hot conditions should consider heat acclimation a key part of their preparation. Whether shooting for the Ironman World Championships in Kona, or an ultramarathon across the Khalahari, these are events in which success is likely to be limited by how well you can cope with the heat. To prep effectively, we therefore recommend commencing an initial heat tolerance test ~4 weeks out from race day, and planning for betweeen 5-10 heat acclimation sessions across that time. However, everyone is different, and with individual circumstances it’s important to build a plan that works perfectly for you, so to discuss your needs more thoroughly with a member of the team, you can drop us a message below!